Our History

From Indigenous peoples who first stewarded the land to modern-day programs that foster outdoor learning, our shared history spans thousands of years.

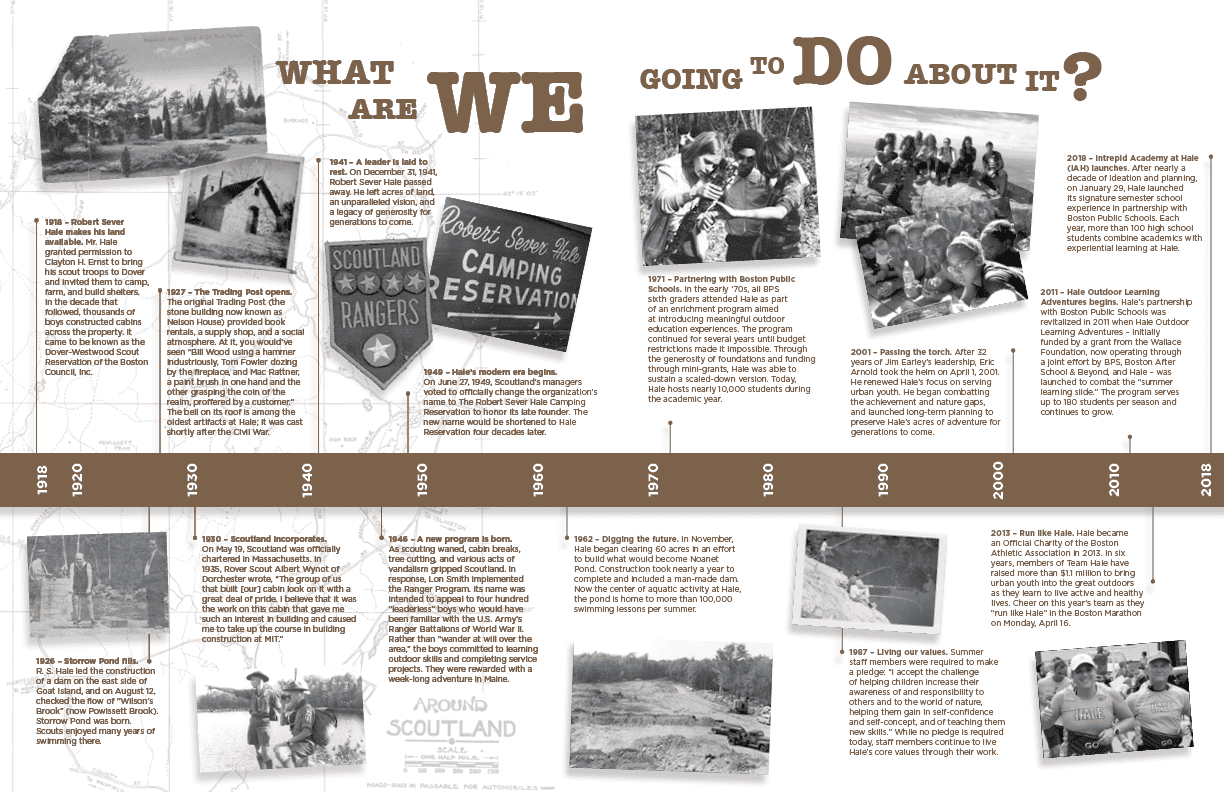

Timeline

For thousands of years, an Algonquian tribal federation called the Moswetuset—later known as the Massachusett, which translates to “people of the great hills”—occupied what is now eastern Massachusetts. Its tribes included the Powissit, Cowate, Natick, Ponkapoag, Neponset, Pegan, and Wisset, among others.

At first, entire tribes moved with the seasons: in the summer, they lived in communal longhouses as they fished and shell fished near the coast; in the winter, they lived in single-family wetus and wigwams as they hunted further inland. Over time, however, the advent of farming resulted in more permanent settlements.

Tradition suggests that one such settlement existed south of Hale’s property, in an area known as Powisset Plain. Archaeologists from Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology have determined such sites were in use as early as 3,000 B.C.

At Hale, artifacts support this theory. Carby Street, formerly known as “Old Indian Path,” leads to a Native American campsite near Storrow Pond. Its inhabitants quarried felsite—a dense igneous rock that they knapped into arrowheads and tools, such as scrapers, knives, and drills—at nine known sites throughout Hale. They also used a stone adze to carve dugout canoes, which suggests they harvested natural resources from marshland that is now Noanet Pond: reed to make sleeping mats and cover shelters, cattail fluff to pad infants’ breechcloths and diapers, and wild rice to supplement meats, fruits, nuts, and vegetables.

Unfortunately, Europeans brought disease, war, and oppression to North America. The Massachusett Federation lost its language and customs as settlers forced its tribes to assimilate. A smallpox epidemic in 1633 ravaged southern New England and further reduced the native population. Descendants of survivors continue to live near Hale and frequent the property today.

Notes from Ernest J. Baker tell us that in 1645, Rock Fielde—the seven acres immediately north of present-day Carby Street—was sold to Edward Hawes by Dedham’s first teacher, Ralph Wheelock. He and other early settlers built an extensive network of stone walls to mark property boundaries and confine livestock. These can still be appreciated throughout the property today.

Throughout the late 1600s and 1700s, settlers regularly harvested local cedar trees to make clapboards and build split rail fences. Deeds suggest a sawmill stood on Rock Meadow Brook, and the remains of a charcoal kiln were once visible near Powissett Pond. They also built “cart roads” so that teams of oxen could pull carts of timber and charcoal out of the woods for Boston’s ship building and iron industries. By 1717, Old Indian Path “had become so important that the town1 found it necessary to take it over and lay it out as a town road.” The road’s early monikers included the “Road Leading to Dover,” the “Highway Leading to the Wilderness,” and the “Road Leading to Cedar Swamp.” But it wasn’t until the early 1800s that it would be renamed for the Carby family, who operated a farm near Cat Rock.

As settlers felled trees and farmed, their desire to protect livestock intensified hunting and trapping. Beavers, raccoons, wild turkeys, deer, and even moose were frequently sighted, and settlers were known to use them for food and clothing. But the area was also “‘infested with wolves, bears, and wildcats, as well as foxes and other predatory animals.’” By 1647, Dedham declared that wolves in particular were “‘greatly anoysome’” to cattle and doubled its ten-shilling bounty to twenty shillings per head. Bears were eradicated by 1730, and the last moose was seen in 1745.

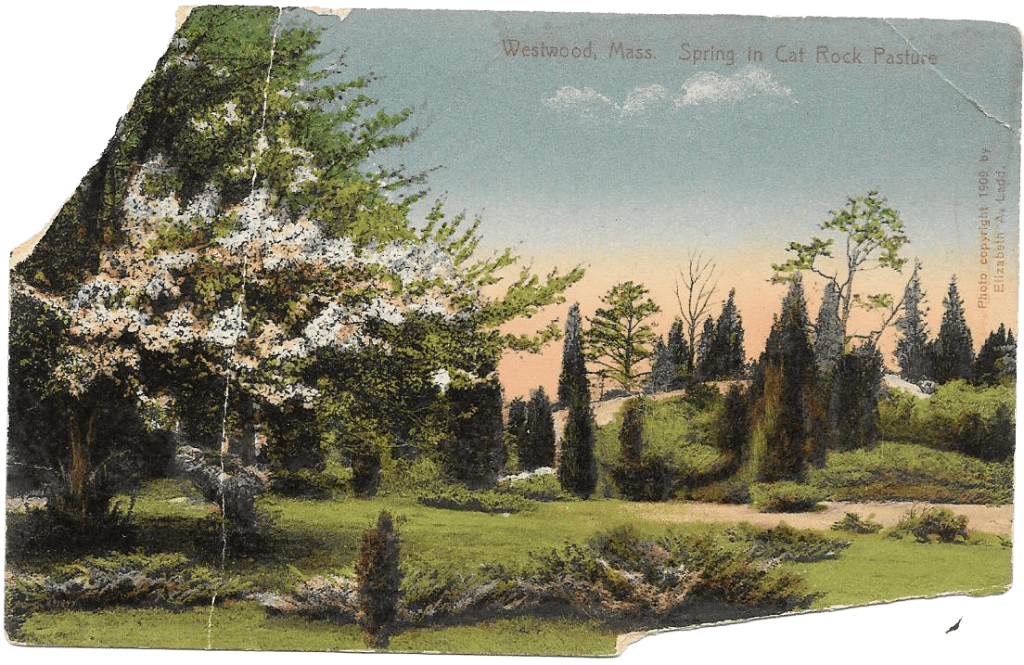

Less is known about what happened on the property during the following century, but we believe farming and logging likely subsided as the Industrial Revolution reshaped the nation’s economy. This change would have given way to the second-growth forest we see at Hale today. By the early 1900s, bucolic Cat Rock Pasture was postcard-worthy.

1 of Dedham; Westwood didn’t incorporate until 1897.

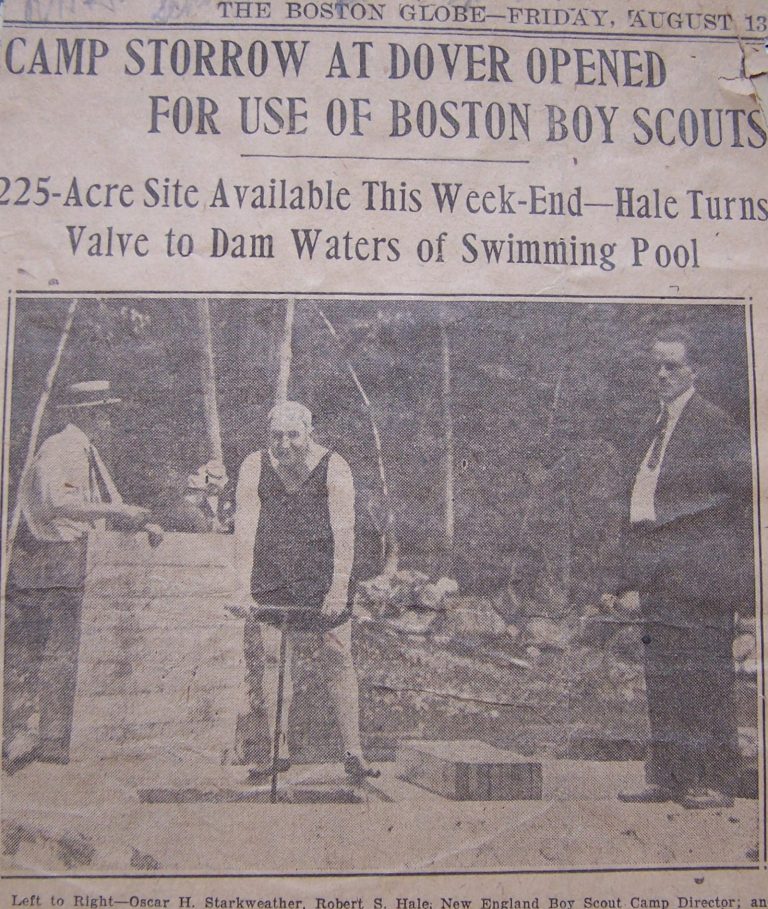

The Boy Scouts of America was chartered in 1910, and soon after that, local scouts began exploring the property. On March 11, 1918, Robert Sever Hale officially invited them to use his land, and by 1923, camping was in full swing at Hale.

Mr. Hale led the construction of a dam on the east side of Goat Island2 in 1926. On August 12 of that year, he checked the flow of Wilson’s Brook (now Powissett Brook) and Storrow Pond resulted. The camp’s original building, “a picturesque log hut3 constructed under the directions of Herman Templeton, a Rangeley, Maine, guide who [taught] the scouts woodcraft,” stood on its shore.

Nelson House (at that time known as “Ye Olde Trading Post,” and later referred to as “The Chapel”) was also erected between 1925 and 1927, purportedly by Italian bricklayer Rumelio Luttazi. Nelson House was originally used to sell canned goods and rent pup tents, blankets, mattresses, and water bags; it was subsequently converted to serve as a place of nondenominational worship. Restored4 in 1961 and renamed yet again, it is now officially The Robert Sever Hale Memorial Building.

In the 1930s, a new Trading Post appeared across the street. Campers gathered there to purchase supplies and recount stories. After numerous additions and renovations, this Trading Post was demolished in 2008. The present-day Trading Post stands on its footprint.

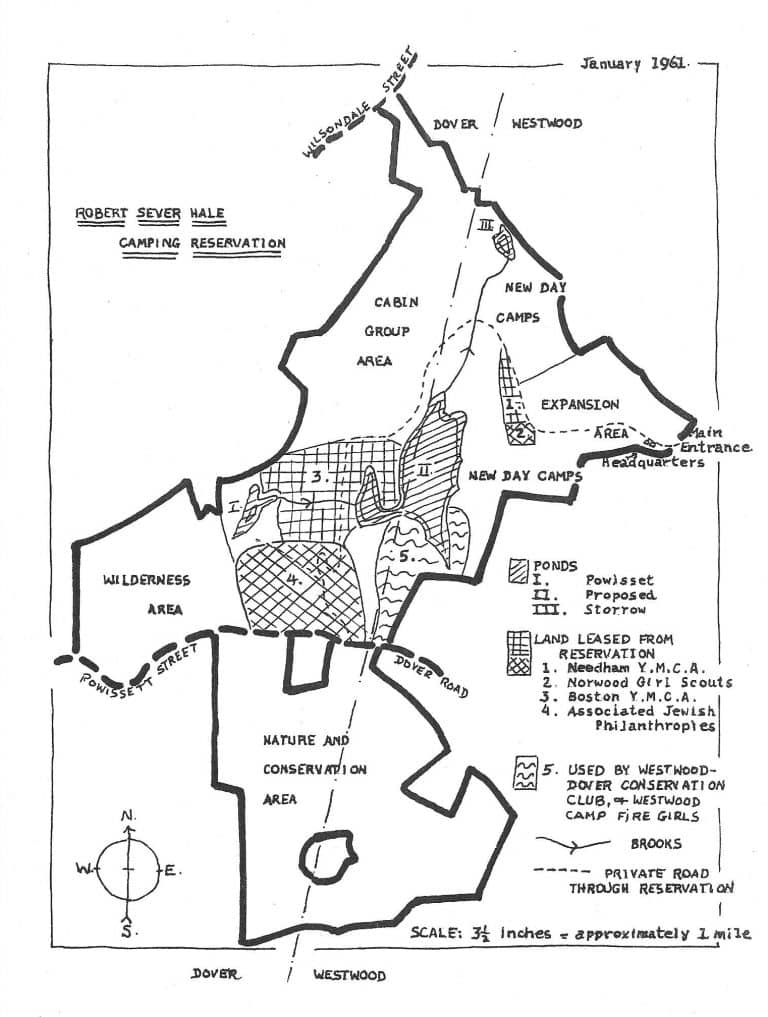

Scoutland continued to thrive during the 1930s under the direction of Mr. Hale. Scouts built more than 40 cabins throughout the property; the present-day Carby House and Main Office served as the ranger’s and superintendent’s homes (respectively). Dover Road was described at that time as a “winding, tortuous route through wild, rocky country,” and as the reservation expanded, Carby Street—a “narrow rough road bordered by a second-growth forest…for hardy souls only”—served as its primary entrance, although Grove Street was used as well. Powissett Pond served as Hale’s go-to spot for a quick dip; scouts, as well as residents who purchased club memberships, were free to enjoy its 12 acres of water.

Throughout his time as head of Scoutland, Mr. Hale regularly wrote and published The New England Steam Kettle. In it, he described himself as an individual who wanted to let readers know what he and others thought. The publication served as a clearinghouse for anyone who wished to express their own ideas and opinions, and he honored authors’ requests for anonymity and eagerly solicited subscriptions, news, and controversial articles.

“The Steam Kettle,” Mr. Hale wrote, “aims to have hot water up to its neck while it sings merrily all the time. The fuel for its fire is provided by Robert. S. Hale as chief offender.” Readers could purchase issues in person for 3 cents per copy, or pay 5 cents per copy to receive the publication by mail.

Mr. Hale passed away on Dec. 31, 1941 and bequeathed his land so that it could be used “to develop intelligent, capable, and responsible citizens.”

2 Goat Island refers to the large rock on the shore of Storrow Pond.

3 built in 1926 and destroyed by fire in the early 1950s; its chimney (built in 1928) remains.

4 under the direction of Louis Grunner and Walter W. Nutile.

Over time, the organization’s attention turned away from scouting and it began to develop its own programs. The “Rangers” program emulated military battalions and practiced leadership skills as they stewarded the property during hard times, and in 1949, the organization was renamed in Mr. Hale’s honor. But by the mid-1950s, it was in a full-blown financial crisis.

Having relied too heavily on the United Community Services (UCS) for income, Hale’s board was faced with a most difficult decision when UCS dissolved the partnership: Should they sell a significant piece of the property to salvage what they could for the future?

Hale was never a cash-rich organization, and hundreds of acres would surely appeal to residential builders looking for land in the beautiful suburbs of Boston. Others hoped to establish a 70-acre gravel pit on the property. By selling 500 of the more than 800 acres, Hale’s managers hoped to create an endowment large enough to support the remaining 325-acre property.

But on August 15, 1956, a motion to dissolve the board of directors forever changed the trajectory of the organization. A special meeting of managers convened to better represent participating agencies and “avoid liquidation of any of the [property] and to maintain it intact as a community asset.”

While this change of heart was a relief, the new board needed a financially viable business plan. They increased programming and made capital improvements to increase interest in Hale. They also entered a 99-year lease with the Jewish Community Center (JCC), which to this day runs Camp Grossman on Hale’s property. Cash from that lease enabled Hale to purchase more land surrounding Powissett Pond and provided funds to create what would become Noanet Pond.

Construction began near the end of 1962, as confirmed by then-executive-director Lon Smith’s late-October statement to The Westwood Press. He announced that the U.S. Soil Conservation Service5 and Norfolk County Soils Conservation District would support the design and construction of the 1,200-foot dam. Great care was taken to perform water drainage studies for the 60-acre pond, and engineer Henry Ritzer was personally commended for generously lending his time and expertise to the endeavor.

By the mid-1960s, Noanet Pond—its name appropriated from a fictional account6 of an actual Native American chief—was open for use. Capable of serving up to 600 families, the property’s new focal point offered members-only access to two beaches. Members of the Dover-Westwood Conservation Club (now Hale Summer Club) frequented the pond’s southern shore. Its northern shore was (and continues to be) “reserved for youth charity organizations from Metropolitan Boston.”

There was a problem, though: Smith and his team had secured funds for the dam, beaches, roads, and parking lots, but they had yet to raise enough money for facilities. The impact of this is still evident: while beautifully landscaped, Hale Summer Club and North Beach feature few permanent structures. The recent construction of new bathrooms at Hale Summer Club brought Hale one step closer to fully realizing the Noanet Pond Construction Committee’s vision for the area.

As the environmental education movement gained traction in the ‘60s and ‘70s, Executive Director James Earley recognized that society’s attention was turning to the natural world and he began repositioning Hale as a “center for outdoor education in the community and in the area.” In 1969, The Patriot Ledger reported on his plans for a new trail system7 that would include trails for people with disabilities and expand public access. Numerous schools started participating in Hale’s programs. Hale Day Camp and the Official Partner Camps of Hale thrived under his leadership. Earley doubled down on Mr. Hale’s focus on serving youth, particularly “overlooked” teenagers in need of “wise recreation.”

5 The U.S. Soil Conservation Service is now known as the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. Congress established the agency in 1935 when it recognized that wasting natural resources such as soil and moisture menaced national welfare. Hugh Hammond Bennett, a surveyor and the agency’s first chief, believed that “land must be nurtured; not plundered and wasted.” Its work was supported by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Civil Works Administration (CWA), and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Since 1944, SCS, now NRCS, has constructed nearly 11,000 dams on some 2,000 watershed projects that continue to provide flood control, water supplies, recreation, and wildlife habitat benefits.

6 King Noanett written by Dedham resident Frederic Jesup Stimson in 1895.

7 including the Allan S. Beale Nature Trail and Split Rock Trail.

Hale’s past is echoed in today’s programs. We continue to provide first-rate outdoor learning opportunities through our summer camps, family and community programs, after-school clubs and extracurricular activities, experiential learning programs for schools and colleges, youth leadership development programs, and professional development for adults.

Since Executive Director Eric Arnold’s tenure began in 2001, we’ve substantially expanded our academic, community, and corporate partnerships as well. Collaboration with Boston Public Schools gave rise to Hale Outdoor Learning Adventures and Intrepid Academy at Hale. And in accordance with our values and through the generosity of our donors, we welcome the public to responsibly recreate here.

As we look to the future, we continue to appreciate the shared history of our land and organization. Mr. Hale expected that his property would be used to develop intelligent, capable, and responsible citizens. We’re proud to carry that mission forward into Hale’s next century.

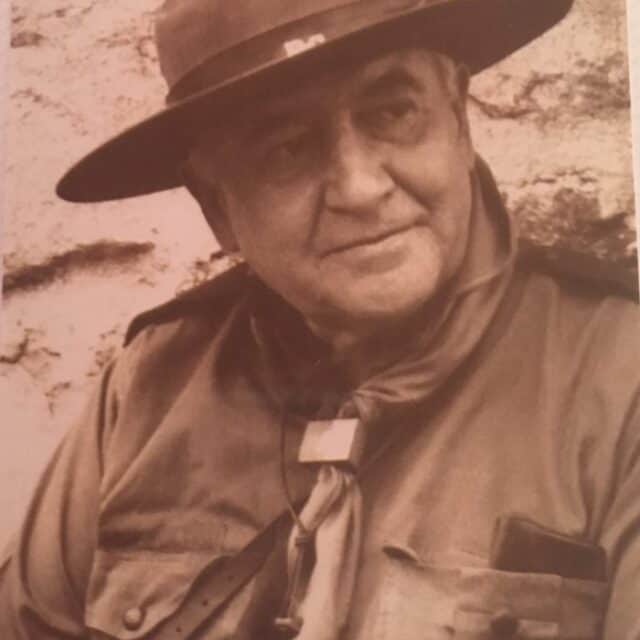

Founder

Robert Sever Hale was born to George Silsbee Hale, a prominent attorney, and Ellen Sever Hale on October 3, 1869. He graduated from Harvard in 1891, completed a two-year graduate course in mechanical lines at Cornell in 1893, and went on to work as a research engineer at the Edison Electric Illumination Company. A “wealthy society man” whose family maintained homes in Boston’s Back Bay and Bar Harbor, Maine, Mr. Hale took up residence at the exclusive Tennis and Racquet Club.

While at Lucerne in 1912, Mr. Hale met 27-year-old milliner and international beauty prize winner May N. Wilson of Boston. Ms. Wilson was a daughter of John T. Wilson of Glasgow. The two were married in Boston by the Rev. Dr. A. A. Berle on December 23, 1913. A “society sensation,” their wedding made national news and was announced in the New York Times, Chicago Daily Tribune, and San Francisco Call and Post, among others. The couple boarded the Lusitania and honeymooned abroad.

It was during the final years of Mr. Hale’s marriage (which ended in 1922) that Lord Robert Baden-Powell, who is widely regarded as the father of the scouting movement, wrote Rovering to Success. The book detailed how young men could continue their personal development during adulthood. Baden-Powell’s service-based philosophy captivated Mr. Hale, who by 1918 had already begun permitting local Boy Scout troops to use his land (known at that time as the Dover-Westwood Scout Reservation). A staunch advocate of self-reliance, he began publishing newsletters in earnest and quickly established the epicenter of Rover Scouting in New England.

In the midst of the Great Depression, Mr. Hale chartered Scoutland with his brother, Boston lawyer Richard Walden Hale, on May 19, 1930. Throughout the following decade he led various efforts to improve the organization’s communications, finances, infrastructure, and ecosystems. He was a major proponent of education: In addition to launching a book rental program for scouts, Mr. Hale personally funded scholarships for Harvard students to work at Scoutland. In addition to writing extensively about scouting, Mr. Hale published two books, The Language of Economics and Ethics (1936) and The Revolution in Economics (1938). In the latter, he aimed to address “those who are willing to think and decide for themselves upon the gigantic problems which confront so ominously our present civilization.”

Mr. Hale passed away on New Year’s Eve in 1941 at the age of 72.